"DID YOU KNOW"?

Pashmina was the favourite of kings and queens.

historically documented that Napoleon Bonaparte gifted Pashmina shawls to his wife, Empress Joséphine, which were considered a luxury item and a diplomatic gift at the time. This act played a major role in popularizing the "cashmere" shawl among the European aristocracy in the 19th century.

The Role of Pashmina in Diplomacy and Fashion

-

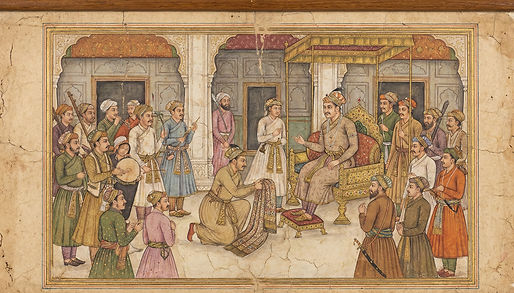

Imperial Gifting: Long before Napoleon, Mughal and Iranian emperors used high-quality Kashmiri shawls as khilat (robes of honor) and diplomatic gifts to signify rank and status.

-

Introduction to Europe: The most common belief is that Napoleon acquired a Pashmina shawl during his Egyptian campaign (1798-1799) and sent it to Joséphine in Paris. Other accounts suggest they may have entered Europe through East India Company officials or merchants in the late 18th century.

-

Empress Joséphine's Influence: Joséphine was captivated by the shawls' softness, warmth, and elegance. She amassed a collection of hundreds and wore them frequently, as depicted in portraits, making them a highly sought-after fashion accessory in French high society.

-

Symbol of Status: Due to the time-intensive, skilled hand-weaving process and the rare, fine wool from the Changthangi goat of the Himalayas, original Pashmina shawls were extremely expensive. They became a powerful symbol of luxury and prestige in Europe.

The Future of Pashmina: From Craft to Collectible

The world of authentic Pashmina is entering a new chapter — a phase where reselling will soon become more common than new manufacturing. The reason is simple: the number of skilled artisans is dropping rapidly, and the few who remain are aging.

A Dying Art: The Average Artisan Is 45+

Today, the average Pashmina artisan in Kashmir is over 45 years old.

Very few young people are willing to take up this craft because:

-

It takes years to learn

-

It offers slow income compared to modern jobs

-

It requires sitting in one position for hours every day

-

A single shawl can take months or even a year to complete

In a fast-moving world, patience has become rare — and so have the artisans who keep this ancient craft alive.

The New Generation Isn’t Continuing the Tradition

Younger people are choosing quicker careers in tourism, trade, IT, and online businesses. The dedication and discipline required for Pashmina weaving — sometimes 8–12 hours a day on a manual loom — no longer appeals to them.

As a result, the number of Pashmina weavers and embroiderers is dropping every year.

A Luxury Turning Into an Asset

Because manufacturing is declining, authentic handmade Pashmina shawls are slowly becoming rare collectibles.

Just like gold, real Pashmina has:

Long-term value

A true handwoven Pashmina never loses value — only appreciates.

Limited supply

With fewer artisans, new pieces will become extremely limited.

Heritage appeal

Every shawl carries history, culture, and identity — something machines can never replace.

Intergenerational worth

A real Pashmina can last over 100 years if cared for properly.

Families often pass them down just like jewelry.

Rising resale demand

Because production is slowing, future buyers will depend on resellers, collectors, and inherited pieces, not new manufacturing.

The “Ring Test” is not a myth

Authentic, handwoven Pashmina is so fine and soft that a full-sized shawl can pass through a ring. This test has been used for centuries to prove purity.

Pashmina is ultra-fine, soft cashmere wool from Himalayan Changthangi goats, prized for its exceptional warmth, lightness, and fineness (under 15 microns), with authentic shawls often passing through a ring as a softness test. It's a rare, handcrafted luxury from the high-altitude regions of Ladakh and surrounding areas, requiring wool from 3-4 goats for one shawl, making it an expensive, coveted textile that takes artisans years to produce.

Pashmina Once Had the Value of a Palace — And Here’s Why

In the era of the Mughals, Afghan rulers, and the early Dogra Maharajas, a true hand-woven Pashmina shawl wasn’t just clothing — it was royal currency. A single masterpiece could be exchanged for land, estates, or the cost of constructing a small palace. These shawls were so precious that emperors often gifted them to foreign dignitaries as symbols of unmatched Kashmiri artistry.

A few little-known facts:

-

Shah Jahan considered Pashmina equal to gemstones and ordered special ateliers where only the most skilled craftsmen were allowed to weave for the royal family.

-

Akbar created an entire grading system for Pashmina, with the finest grade reserved solely for the emperor.

-

European courts in France, Russia, and England paid fortunes for Kashmiri shawls. Some queens owned collections valued higher than their entire jewellery chambers.

-

By the 18th century, Pashmina was one of the most expensive luxury goods in the world, often transported with armed guards on trade routes because of theft risk.

-

In many royal dowries, a “treasure chest of Pashmina” was considered equal to gifting land or gold.

Why such extraordinary value?

Because a real Pashmina required:

-

Wool collected from Himalayan Changthangi goats at 14,000 ft

-

Months of hand-spinning by expert women spinners

-

Years of weaving and embroidery

-

Zero machinery — only skill, patience, and precision

-

Knowledge passed down from father to son, mother to daughter

A single master embroidery shawl could take 1 to 3 years, depending on the motif.

Pashmina wasn’t just a fabric — it was a living symbol of royalty, heritage, and human devotion. And even today, a true handmade shawl carries the same soul, rarity, and value that once placed it on the same level as palaces and gemstones.

Each Shawl Passes Through 6–10 Artisans — A Journey of Pure Human Craft

A true Kashmiri Pashmina is never the work of one person. It is a chain of mastery, where every artisan contributes a piece of their life, skill, and heritage to create one masterpiece.

From the mountains of Ladakh to the looms of Srinagar, a single shawl travels through 6–10 highly skilled artisans, each with a role perfected over generations:

-

The Changpa shepherds carefully collect the delicate under-fleece from Changthangi goats during spring shedding.

-

Women spinners transform the cloud-soft fibres into the thinnest hand-spun yarn — a skill that takes decades to master.

-

Master weavers spend weeks to months weaving the yarn on traditional wooden looms, ensuring the shawl is feather-light yet strong.

-

Dyers use age-old techniques to colour the fabric without damaging its natural softness.

-

Washermen gently treat the shawl in running waters to refine its texture and purity.

-

Embroiderers (Sozni or Tilla artists) invest months — sometimes years — adding motifs that can reach the fineness of painting.

Each artisan works with unmatched patience, knowing they may never see the final customer, but their art will be worn, loved, and passed down for generations.

This is why no two Pashminas are identical — each carries the signature and soul of the hands it passed through.

Only One Goat in the World Can Produce True Pashmina

Pashmina is not just a fabric — it begins with one of the rarest animals on the planet:

the Changthangi goat, also called Changra goat, found only in the high-altitude plateaus of Ladakh and parts of Tibet.

These goats live in some of the harshest conditions on earth:

-

Altitude: 14,000–16,000 ft above sea level

-

Temperature: can drop to –40°C

-

Terrain: cold desert winds, minimal vegetation, extreme isolation

To survive this environment, the Changthangi goat naturally grows an ultra-soft, ultra-fine under-fleece known as Pashm.

This inner layer is what becomes true Pashmina.

Here are the fascinating details:

-

Fibre Fineness: as fine as 12–16 microns, thinner than human hair

-

Collection Method: the fleece is not shaved — it is combed out gently by hand only once a year during the spring moulting

-

Rarity: each goat provides just 80–150 grams of usable fibre per year — barely enough for one pure Pashmina scarf

-

Exclusivity: no other goat breed in the world — not even cashmere goats — produces fibre of this softness, warmth, or natural length

-

Natural Insulation: Pashmina can retain heat 8 times better than sheep wool

This is why authentic Pashmina is priceless:

its raw material comes from a single rare animal, living in a single rare climate, producing a single rare fibre — once a year.

Pashminas Were Once Measured in Years, Not in Price

In the era of the Mughals and early Maharajas, a Pashmina shawl was far more than a garment — it was a measure of time, skill, and human devotion.

Asking for the price of a shawl was considered disrespectful. Instead, people would ask:

“How many years did it take?”

Because in those days, the true value of a Pashmina came from the years invested:

-

Months of spinning ultra-fine yarn by hand

-

Long seasons of weaving on traditional looms

-

Years of embroidery, sometimes done by a single artisan

-

Generations of skill passed from master to apprentice

The longer a shawl took to create, the higher its prestige and the more royal its status.

A Pashmina that took 5–10 years to complete was considered a treasure fit for kings — often stored in royal treasuries alongside jewels.

Even today, the time woven into a Pashmina is what makes each piece priceless.

Some Heirloom Pashminas Have Survived 200–300 Years

Authentic Pashmina is not just a fabric — it’s a natural heirloom capable of outliving the people who wear it.

In museums across India, France, the UK, and Central Asia, there are Pashmina shawls that are 200 to 300 years old, still intact, soft, and breathtakingly detailed.

This extraordinary longevity comes from the purity of the fibre:

-

Hand-spun Pashmina yarn retains its strength for centuries

-

Natural dyes age gracefully, deepening in beauty rather than fading

-

Traditional hand-weaving creates a structure that resists time

-

Finely crafted embroidery remains vibrant because it is stitched, not printed

Families in Kashmir still pass down shawls as wedding gifts, dowry pieces, and generational treasures — often wrapped carefully in mulmul cloth and preserved like jewels.

A true Pashmina is made slowly, loved deeply, and cherished long after its original owner is gone — a timeless piece of art that becomes more valuable, more meaningful, and more emotional with every generation it crosses.

Ancient Rulers Used Pashmina as a Symbol of Time and Power

For centuries, Pashmina shawls were not just luxuries — they were symbols of royalty, diplomacy, and prestige.

In the courts of the Mughals, Persians, Central Asian sultans, and early Indian Maharajas, a finely crafted Pashmina was considered one of the highest forms of honour.

Kings gifted Pashmina shawls during:

-

Coronations — to welcome new rulers

-

Royal weddings — as symbols of prosperity and elegance

-

Peace treaties — to seal alliances between kingdoms

-

Diplomatic visits — as a gesture of respect and goodwill

Each shawl represented months or even years of human labour, involving multiple master artisans working with supreme patience.

The immense time woven into a single piece made it more meaningful than gold, jewels, or coins.

To gift a Pashmina was to gift time, artistry, and heritage — a gesture that carried emotional, cultural, and political weight.

Even today, owning a pure Pashmina connects you to the same sense of legacy once reserved for kings.